Cob Research Institute's Cob Code Approved for the 2021 IRC

For the first time, a Cob Construction Appendix has been approved for inclusion in the International Residential for building codes in the United States and a number of other countries.

Also known as “monolithic adobe,” cob is an ancient method of earthen construction, used for thousands of years around the world in regions including Britain, Northern Europe, the Middle East, West Africa, China, and the Southwestern United States. A stiff mixture of clay-soil, straw, water and usually sand is placed in layers to create walls that can support a roof with no need for structural posts. When properly designed, constructed, and maintained, cob homes have proven to last many centuries. Embraced as environmentally friendly, non-toxic, low cost, easy to learn, and artistically inspirational, cob construction has undergone a revival in the United States and around the world since the mid-1990s. However, because there has been no building code for cob, it has been difficult or impossible to obtain permits for cob buildings in most parts of the United States. With the approval of a model cob code this will change, creating the possibility for legal cob construction throughout the US and beyond.

Two-Story cob cottage in Devon, England, built in the 1400's

Modern cob house built in 1990's, Devon, England

What is this New Cob Code?

The new code was developed as a public service by the non-profit Cob Research Institute (CRI), the result of collaboration by dozens of individuals and years of research and testing at several universities and laboratories. The entire cob code and its supporting documents can be found on the CRI website www.cobcode.org. It will be published in August of 2020 as an appendix to the 2021 International Residential Code. The IRC is revised on a triennial cycle, and anyone can submit proposed modifications. In January 2019, CRI submitted its proposed cob code and in May testified in its support before the IRC Committee. The code was initially disapproved by the committee, citing the lack of testing to support the claim of a one-hour fire rating. The CRI team removed the fire rating and re-submitted the proposal in the Public Comment second phase of this code development cycle.

On October 26, 2019, at the IRC Public Comment Hearings in Las Vegas, CRI’s revised code proposal was voted on by ICC voting members in attendance (mainly building and fire officials). The proposal received an overwhelming 93 votes in favor to 6 against, and later garnered the support of at least two-thirds of participating ICC members in an on-line ballot, leading to its official inclusion in the 2021 IRC as Appendix U: Cob Construction (Monolithic Adobe).

While the IRC is a model building code with no legal standing of its own, it is used in most of the United States as the basis for building codes for one-and two-family dwellings, townhouses, and accessory structures. It becomes enforceable through adoption by a governmental jurisdiction such as a state, county or city. State and local jurisdictions have their own schedules for revising and adopting building regulations, typically requiring at least another year or two before new codes are adopted. For example, the 2019 California Residential Code, based on the 2018 IRC, went into effect on January 1, 2020. Check with your local building department or the agency that oversees code adoption in your state to find out when changes based on the 2021 IRC will be enacted in your location.

Furthermore, appendices to the IRC are expressly optional. Unlike the main body of the code, each appendix must be specifically adopted by a jurisdiction to become a part of its building regulations. The public can influence this process by expressing a need for such a code to their local building department or overseeing state agencies. Other natural building systems, including strawbale and light straw-clay, have undergone the same process, first becoming appendices to the IRC, and then being adopted into state or local building codes. For example, IRC Appendix S: Strawbale Construction was approved as part of the 2015 IRC and has since been adopted by at least six states and nine city or county jurisdictions.

Even before the cob code is adopted for your location, it could still help you obtain a permit for your cob building project. All building codes contain a provision called Alternative Methods and Materials Request (AMMR), which allows approval of building systems not included in the code if it can be demonstrated to the building official’s satisfaction that the alternative is “at least equivalent of that prescribed.” To date most permitted cob buildings in the US have used this approach, but the process of compiling the evidence needed to support the permit application is often arduous. The publication of Appendix U should go a long way towards reassuring officials that cob buildings can be a safe and reasonable alternative. Even before adoption, Appendix U can be proposed to a local building department for use on a project basis.

First permitted cob structure in Berkeley, California under construction in 2017 and completed

How the Code Effort Began

The Cob Research Institute is a non-profit organization started in 2008 with the mission “to make cob legally accessible to all who wish to build with it.” It was founded by Bay Area architect John Fordice, who fell in love with cob after attending a hands-on cob building workshop in 1996. The class was led by by Ianto Evans of the Cob Cottage Company, the first group to reintroduce cob construction to North America in the 20th Century. Frustrated by the difficulty of obtaining legal permission for cob buildings, Fordice passed the hat at a Natural Building Colloquium and raised enough money to file for official non-profit status. He assembled a volunteer Board of Directors and began combing through the international literature on the engineering and regulation of earthen buildings, while outlining the necessary testing and other steps towards approval of a cob code.

In 2013, CRI Board members Massey Burke and Anthony Dente, PE of Verdant Structural Engineers collaborated with engineering faculty and students at the University of San Francisco to determine the physical properties such as compressive strength and modulus of rupture of cob mixes with varying amounts and lengths of straw. This led to a series of other research collaborations. In 2018, CRI worked with Santa Clara University to construct four full-size cob wall panels with varying kinds of internal reinforcement, ranging from straw-only to a rebar grid similar to those used to reinforce concrete walls. The panels were attached to a testing frame that applied force to the tops of the walls in back-and-forth cycles that simulate the effects of earthquakes. The testing of these walls under laboratory conditions, along with other testing, gave civil engineer Dente the data he needed to write the structural sections of Appendix U.

Santa Clara University in-plane reverse cyclic testing (left) and Cal Poly University out-of-plane testing (right)

Another key member of CRI’s team is Bay Area architect Martin Hammer. Hammer is a long-time ecological building advocate who has been involved with code-writing efforts for decades. He was the primary author of IRC Appendix R: Light Straw-Clay Construction and IRC Appendix S: Strawbale Construction, among others. His familiarity with the ICC process and personnel, along with that of colleague David Eisenberg, were critical factors in the success of this endeavor. The team also solicited input from over a dozen experienced cob builders, six civil engineers, and four architects, including Graeme North, chair of the committee that developed the seminal New Zealand Standard for Earth Buildings. The New Zealand Standards are among several earthen building codes and standards that also informed Appendix U.

Further Testing is Still Needed

Although the adoption of Appendix U is a major accomplishment for CRI, the group has its future work cut out for it. The team plans to improve the code in future IRC cycles to make it more useful to designers, builders and homeowners in more diverse geological and climatic areas. The highest priorities for continued testing and research include fire resistance, thermal performance, and additional reinforcement options.

The rising frequency and intensity of wildfires that have devastated Australia and western US states in recent years have brought increasing scrutiny to the fire safety of our homes and communities. Earthen building materials could provide part of the solution. In bushfire-prone Australia, earthen walls have been classified along with masonry and poured concrete as the most fire-resistant building techniques known. Although cob is so fireproof that it is commonly used to build fireplaces and wood-fired ovens, the code approval process requires testing to a national standard by a certified laboratory in order for a building system to receive a fire-resistance rating. CRI is currently collaborating with Quail Springs of Southern California to procure the testing required to demonstrate a one-hour or greater fire rating, which would allow cob to be used close to property lines (where it could help stop the spread of fires) and as a common wall between residential units.

One of the most significant remaining obstacles to the legal construction of cob is complying with the energy conservation requirements of the IRC (or your state’s energy code). A building’s thermal performance depends on both the mass and thermal resistance (insulation value) of its thermal envelope, in the context of the local climate; energy codes take all of these factors into account. Cob walls have high thermal mass, which is very beneficial in warm climates or seasons, but low thermal resistance, which is especially important in cold climates or seasons. Most energy codes consider a cob wall a “mass wall” like concrete block, brick, or rammed earth, which reduces the requirement for thermal resistance. But even in warm climates, it is difficult for cob walls to comply without adding some type of insulation. For example, California’s energy code requires that an exterior mass wall in Los Angeles have a minimum insulation value of R-8. The cob samples CRI had tested by Intertek Laboratories yielded an R-value of just 0.22 per inch. With that R-value, a cob building in L.A. would need walls 36 inches thick in order to pass the energy code. This is about twice as thick as common cob building practice in North America and could cause structural concerns in high seismic zones.

To address this issue, CRI has begun a project to test both the structural and thermal properties of lower density cob mixes made by substituting lightweight aggregate such as crushed pumice for the sand, and by increasing the straw content. Even these measures will be insufficient in colder regions. A research project called CobBauge, based at the University of Plymouth, England, has been devising ways to insulate cob walls by wrapping them with lighter mixes of clay and natural fibers including hemp and straw. Further research and testing in this arena will be critical to enable cob homes to be built both legally and efficiently across North America and other temperate regions.

The EU-funded CobBauge project aims to develop composite earthen walls with both good insulation and structural qualities.

Another concern is cob’s performance in earthquakes. The IRC divides the United States into Seismic Design Categories (SDC) A through F, based on the likelihood and severity of earthquakes in each locale. Appendix U states that any cob building outside of SDCs A, B and C requires an engineered structural design, typically by a licensed civil engineer. The full-scale testing done with Santa Clara University, along with similar tests in collaboration with California Polytechnic State University, Quail Springs, and Oasis Design, yielded data about the strength of several reinforcement methods that are summarized in tables in the code. The test walls employed a combination of reinforcing strategies which included straw, with and without steel bar and/or steel mesh to strengthen the wall against seismic and wind lateral loads. Other reinforcing combinations, materials and strategies could be tested, including the use of bamboo, fiberglass, basalt fiber and/or plastic mesh and bars, to increase the range of options available to builders and designers. Further testing can also increase our understanding of proper connections between cob walls and foundations and roof assemblies.

Plans to Promote the Cob Code

In addition to further testing, CRI plans to advocate for the adoption of Appendix U by as many building jurisdictions as possible. As evidenced by the ICC vote last October, building officials have shown remarkable enthusiasm for the cob code, presumably motivated by their desire for environmentally responsible and fire-safe building methods. Still, the building regulatory community is understandably conservative, as it is charged with ensuring building safety, and a great deal of education and advocacy will be necessary to bring the code into widespread use.

CRI also intends to create an educational guide for builders who wish to use the code. Building codes can be challenging to interpret, and many people who are drawn to natural building methods lack experience deciphering the technical language. Towards that end, the CRI team is currently drafting the official commentary to be published along with Appendix U next year. This commentary will provide useful background information to help designers, builders and building officials alike understand the intent of the code and how to use it correctly. Appendix U: Cob Construction (Monolithic Adobe) will be an evolving resource for promoting best cob building practices, hopefully encouraging ever greater acceptance of this treasured and time-tested building method.

CRI Needs Your Support

The research, testing, and writing of this Cob Construction Appendix, and its submittal to the ICC for approval have been an expensive undertaking. Although our work has been generously supported through crowdfunding and other donations, as well as by an enormous volunteer effort, the expense of CRI’s successful code effort has greatly exceeded fundraising to date. In order to continue our work, CRI needs your support. If you recognize the value of building with cob, please visit www.cobcode.org and join with CRI to make cob safe and accessible to everyone.

Thank you,

the CRI Team!

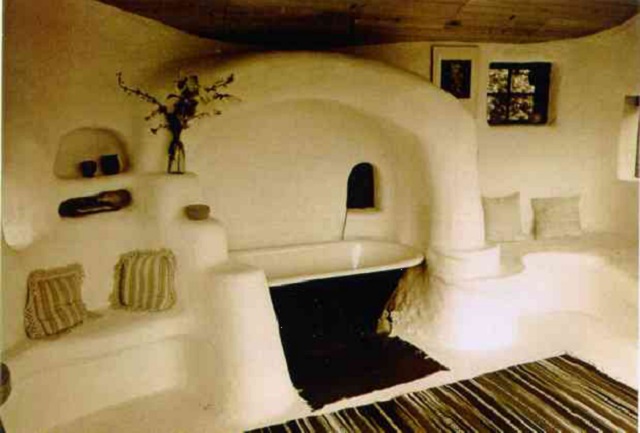

This cob massage studio in Oregon shows off the medium’s sculptural qualities.